White Bear King Valemon

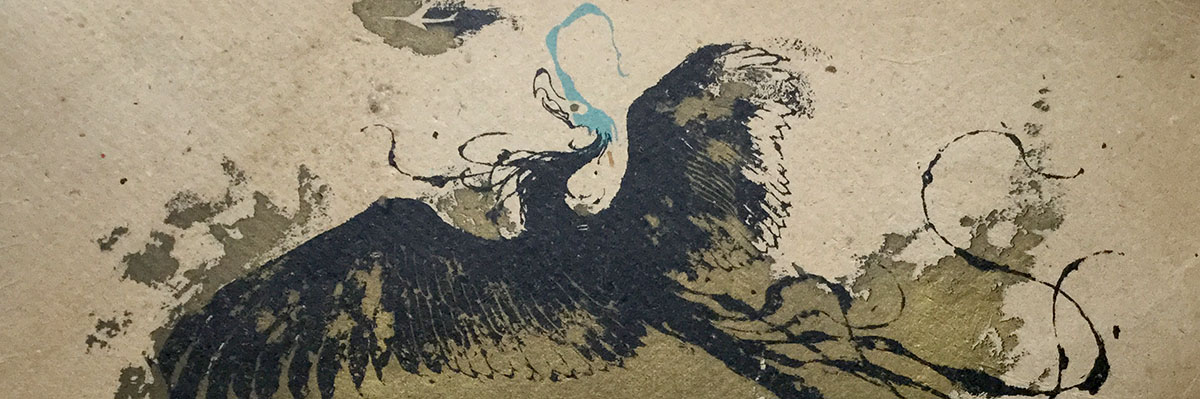

“Once when she was in the wood, she set her eyes upon a white bear, who had the very golden wreath she had dreamt of between his paws.”

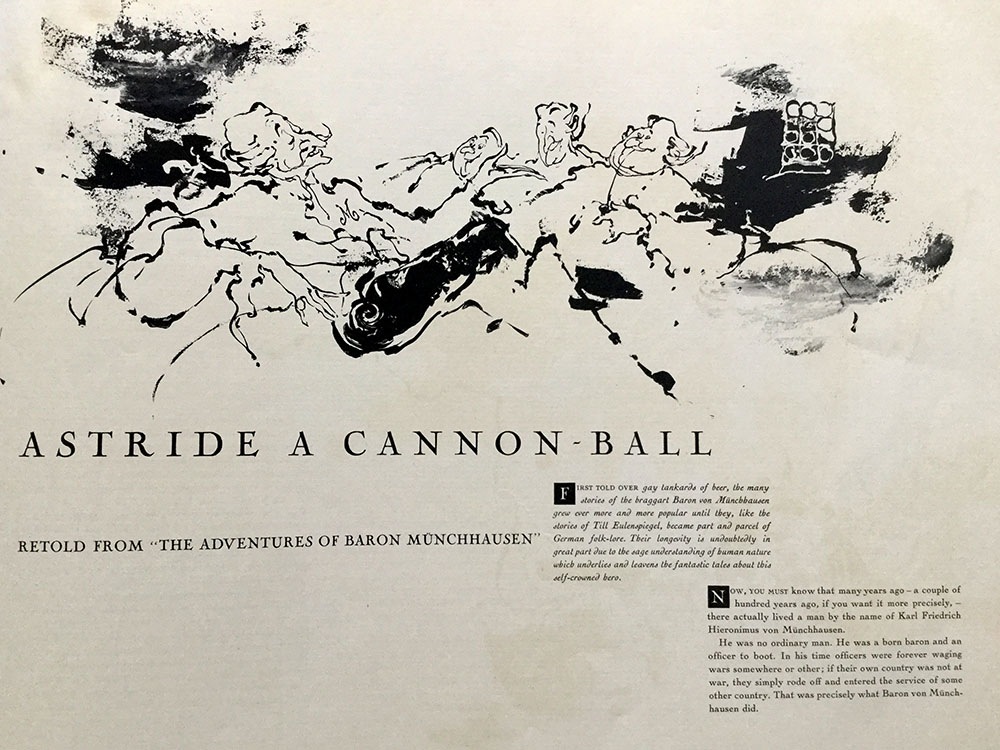

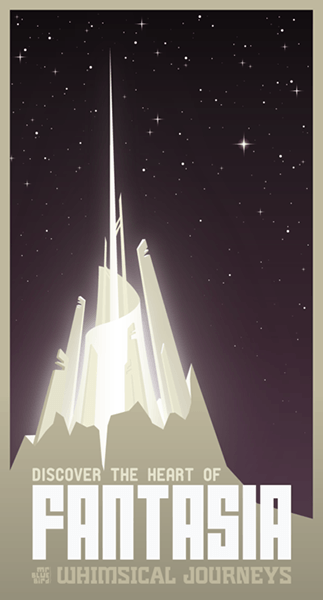

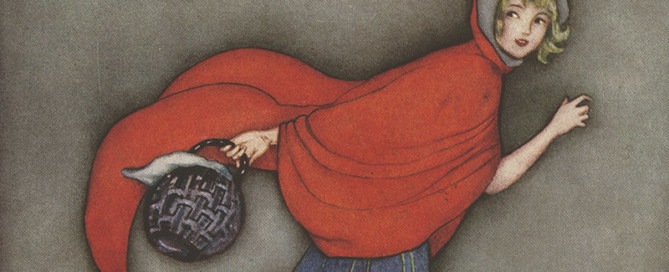

In the nineteenth century, after the Brothers Grimm had published their first collection of stories, Asbjørnsen, a teacher, and Moe, a minister, decided to wander around the Norwegian countryside and collect their own set of wonder tales. Indeed, they corresponded with the Grimms, each approving of the other’s work. Both sets of stories have been illustrated by fantastic artists over the years, including the Norwegian artist Theodor Kittlesen and the Danish artist Kay Nielsen (who later worked on Walt Disney’s Fantastia) who have created some especially beautiful pictures for these stories. Indeed, one of these Norwegian tales, “White Bear King Valemon”—as imagined by Kittelsen—adorns the logo of the Norwegian folklore society.

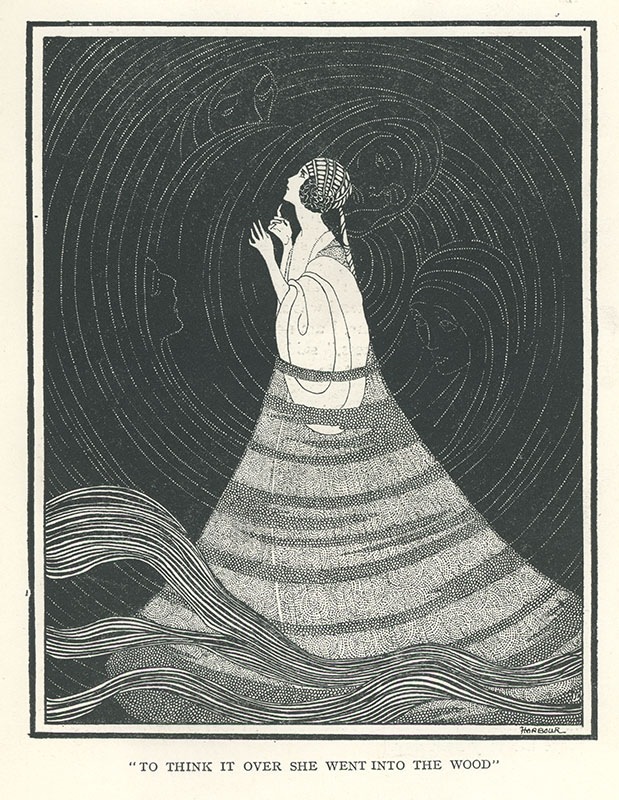

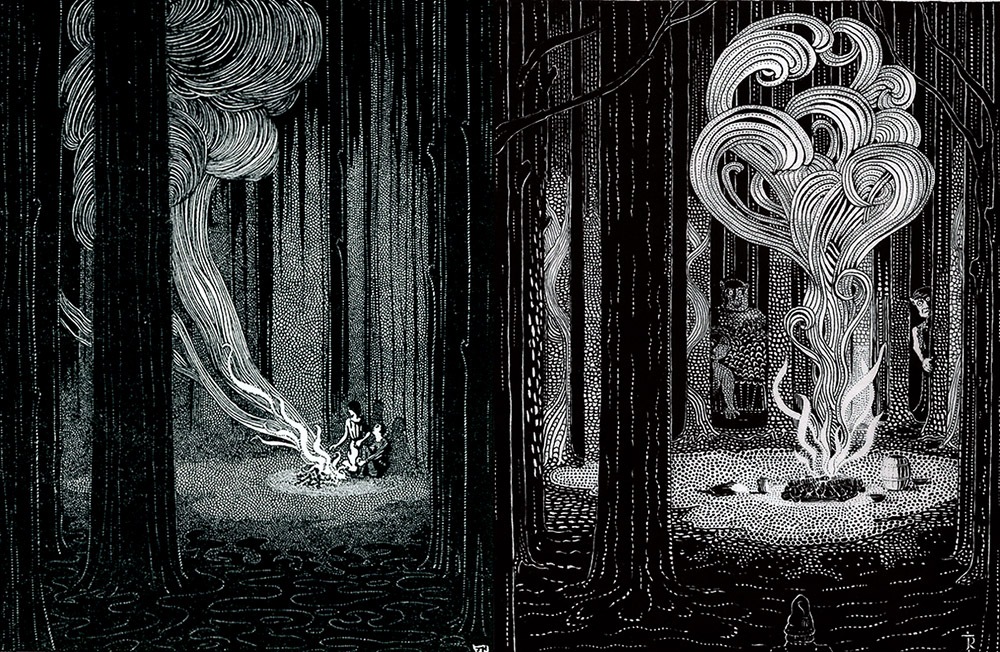

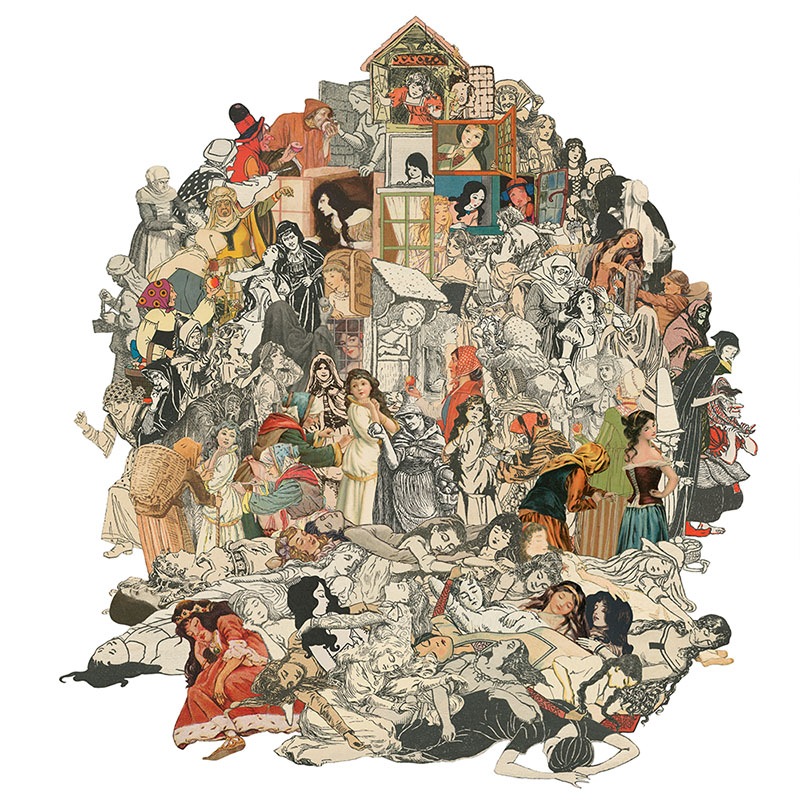

I first encountered this collection of stories when I learned that the American poet Robert Bly was writing a book examining six fairy tales of special importance to him, including “King Valemon.” I was also lucky enough to be asked to remix some old illustrations for this new book. I have included, above, a draft image for publication combining pictures by Kittelsen and Moyr Smith (though the final version differed significantly). As you read the tale of “King Valemon,” as translated by Sir George Webbe Dasent and edited by me, I have also woven in several other illustrations of this tale, though it is somewhat less frequently pictured than it’s Aarne–Thompson-Uther type 425A sibling, “East of the Sun and West of the Moon.”

I hope you enjoy the story of the white bear, the young princess, and the troll enchantress.

White Bear King Valemon

Once upon a time there was a king with two daughters who were ugly and evil, but a third who was as fair and soft as the bright day. One night, his third daughter dreamt of a golden wreath so lovely that she couldn’t live without it. She grew sullen and wouldn’t so much as talk due to her grief at not having the wreathe, so the king sent out a pattern based on her dream to goldsmiths far and wide to see if they make the wreath. The goldsmiths worked night and day, but the princess tossed all their wreathes away.

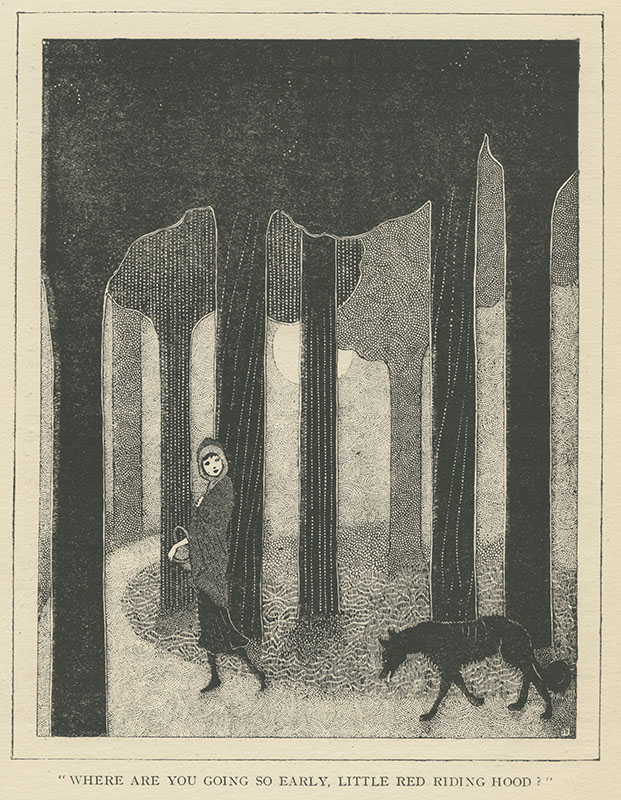

But once when she was in the wood, she set her eyes upon a white bear, who had the very wreath she had dreamt of between his paws and was playing with it. The princess wanted to buy it, but the bear said she could only have it if he could have her. Because she thought life was not worth living without the wreathe, she agreed to be fetched in three days, on Thursday.

When the princess arrived home with the wreathe, everyone was overjoyed that she was happy again. The king thought that it should not be so hard to stop a white bear from taking his daughter, so three days later put his whole army around the castle to turn away the bear. But when the white bear came, no weapon could scratch his hide and he hurled the soldiers left and right so that they lay in piles. Upon seeing this, the kind send out his eldest daughter instead of his youngest, and the white bear took her upon his back and went off. When they had gone quite far, and farther than far, the white bear asked her,

Have you ever sat softer, and have you ever seen clearer?”

“On my mother’s lap I sat softer, and in my father’s hall I saw clearer,” she answered.

“Oh!” said the white bear, “Then you are not the right one,” and he chased her home.

The next Thursday the bear came again, and it went just the same. The army went out, but neither iron nor steel scratched hide, and he mowed them down like grass until the king begged him to stop. The king sent out his next oldest daughter, and the white bear took her on his back and went off. When they had traveled far and farther than far, the white bear asked,

“Have you ever seen clearer, and have you ever sat softer?”

“Yes,” she answered. “In my father’s hall I saw clearer, and on my mother’s lap I sat softer.”

“Oh! Then you are not the right one,” said the white bear, and he chased her home.

On the third Thursday the bear came again, and he attacked the king’s men harder than before. As the king could not let his whole army be slain, he gave the bear his youngest daughter. The bear took her on his back and went far away and farther than far. When they had gone deep, deep, into the woods, he asked her as he had asked the others, whether she had ever sat softer or seen clearer.

“No, never!” she said.

“Ah!” he said. “You are the right one.”

They came to a castle so grand that her father’s looked like the poorest place in the world by comparison. The princess was to live there with no responsibility other than seeing that the fire never went out. The bear was away by day, but with her at night in the form of a man. All went well for three years, but every year she had a baby and the bear carried each off as soon as they came into the world. The princess grew bored, and begged to go home to visit her parents. There was no stopping her, but the bear made her give her word that she would listen to her father and not do what her mother wished. So she went home, and when she was alone with her parents and told them how she was treated, her mother wanted to give her a light to take back that she might see what kind of man she was with.

Her father, however, said, “You must not do that, for it will lead to harm and not to gain.”

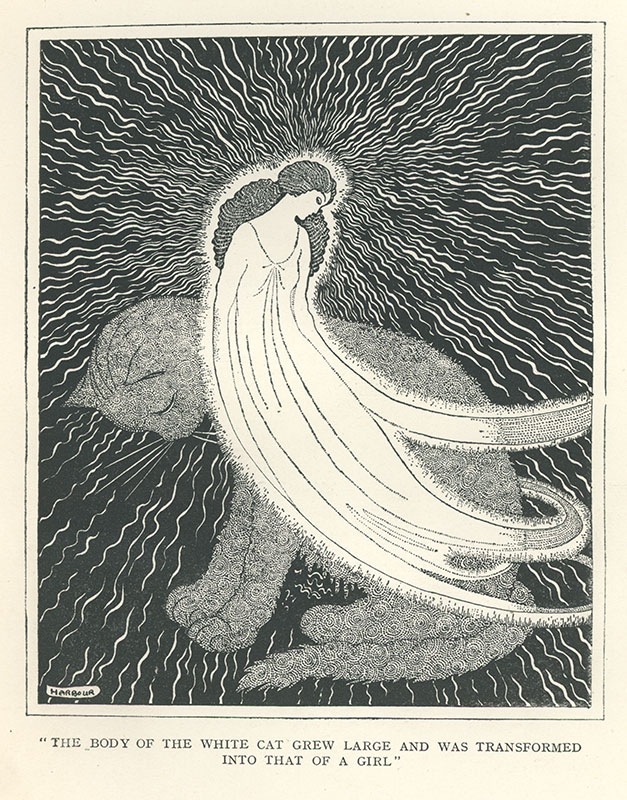

But however it happened, so it happened, the princess took a bit of a candle-end back with her. The first thing she did on her return, when her bear-by-day was sound asleep, was to light it and illuminate him. He was so lovely that she thought she could never gaze at him enough, but as she held the candle over him a hot drop of tallow dropped on his forehead and he woke up.

“What is this you’ve done?” he said. “Now you have made us both unlucky. There was no more than a month left, and had you lasted it out, I should have been saved and my curse broken. A hag of the trolls has bewitched me to be a white bear by day, but now that you have broken your word I must go marry her.”

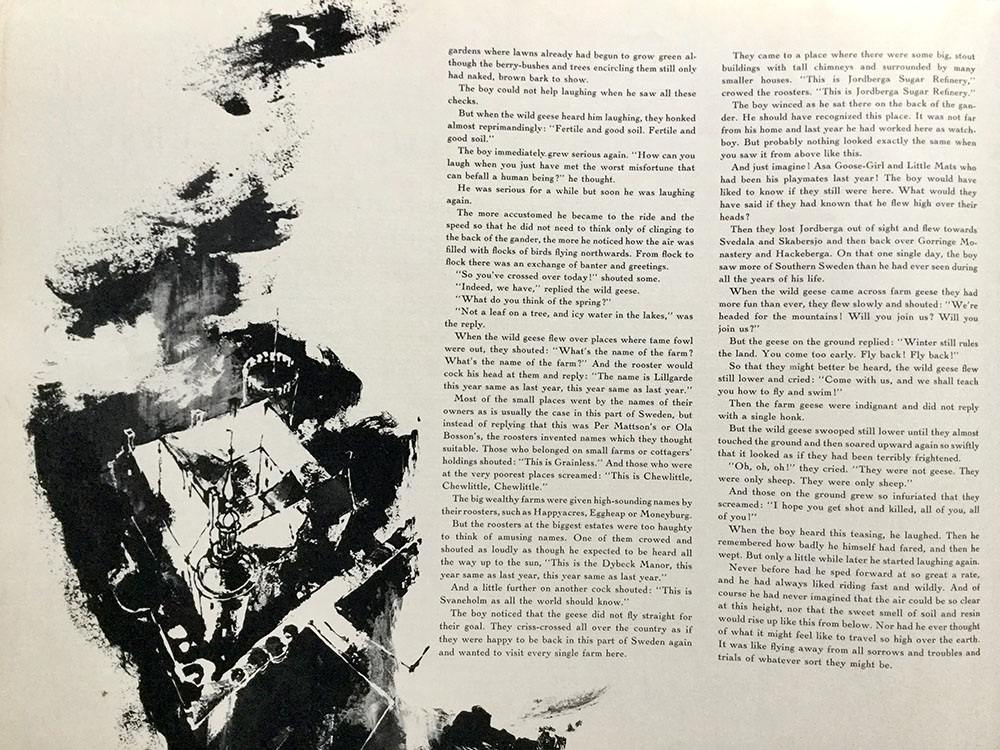

She wept and lamented, but he had to go. She asked if she could go with him, and he replied, “No, there is no way to do that.” Still, when he set off in his bear-shape, she took hold of his shaggy hide, threw herself upon his back, and held on fast.

Away they went over crags and hills, through brakes and briars, till her clothes were torn off her back. Finally, she was so tired, that she lost her wits and let go. When she came to, she was in a great forest. She set off again, but could not tell where she was going. After a long, long, time she came to a hut with an old woman and a pretty little girl. The princess asked them whether they had seen anything of King Valemon the white bear.

“He passed by here this morning early,” they said. “But he was going so fast that you’ll never be able to catch up.”

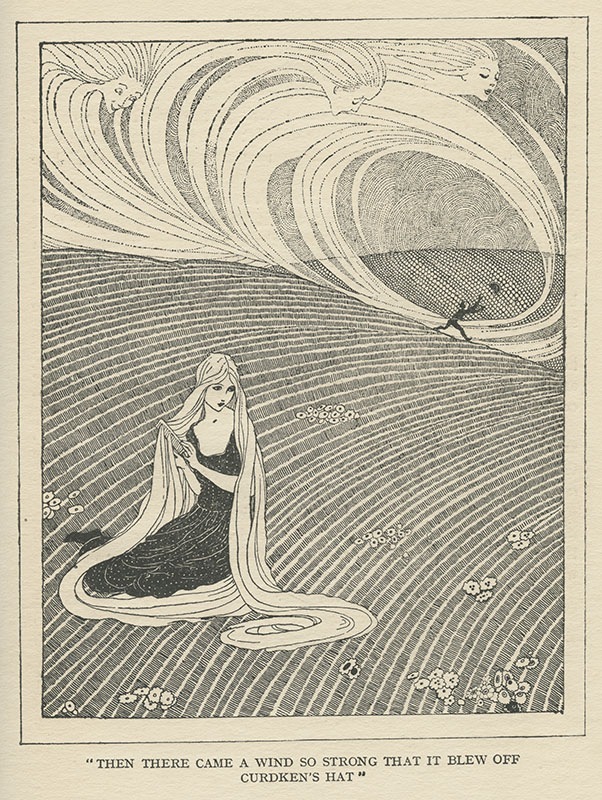

The little girl there ran about, playing and clipping the air with a pair of golden scissors. As she clipped, silk and satin flew all about. Where the scissors went, there was never any want of clothes.

“This woman,” she said, “who has to go so far on such difficult paths, may well suffer much. She will need these scissors more than I do to cut out clothes.”

The child begged the older woman to let her hand over the scissors, until at last she agreed.

Away the princess traveled through woods that seemed endless, both day and night, until she came to another hut the next morning. In it there was also an elder woman and a young girl.

“Good day,” said the princess. “Have you seen anything of King Valemon the white bear?”

“Was it you, maybe, who was to have him?” said the old woman.

“Yes, it was!”

“Well, he passed by yesterday, but he went so quickly that you’ll never be able to catch up.”

This little girl played on the floor with a flask that poured out any drink one wished to have.

“This poor woman,” said the girl, “who has to go so far on such difficult paths, may well be thirsty and suffer much. She will need this flask more than I do.”

She asked the old woman if she could give the princess the flask, and the old woman have her permission to do so.

The princess took the flask, thanked them, and set off again through the woods. After travelling all day and through the next night, she came to a third hut with an old woman and a little girl.

“Good day,” said the princess.

“Good day to you,” said the old woman.

“Have you seen anything of King Valemon, the white bear?” asked the princess.

“Maybe it was you who was to have him?” said the old woman.

“Yes, it was!”

“Well, he passed by here the day before yesterday, but he was going so fast that you’ll never be able to catch up.”

This little girl played with a napkin on the floor. When anyone said to it, “Napkin, spread yourself out and be covered with dainty dishes,” it did just that, so where it went there was never any want of a good dinner.

“This poor woman,” said the little girl, “who has to go so far on such difficult paths, may well starve and suffer other ills. She has far more need of this napkin than I do.” She asked if she could give the princess the napkin, and did so.

The princess took the napkin, thanked them, and set off again. She went far and farther than far through the woods and travelled all day and night. The next morning she came to a mountain as steep as a wall, so high and wide that she could see no end to it. At the base of the mountain there was a hut, and as soon as she set foot inside it, she said, “Good day. Do you know if King Valemon the white bear passed this way?”

“Good day to you,” replied the old woman in the hut. “It was you, maybe, who was to have him?”

“Yes, it was!”

“Well, he passed by and went up the mountain three days ago, but nothing else without wings can climb it.”

The hut was full of small children who hung around their mother’s skirts and bawled for food as she put a pot on the fire full of small, round pebbles. The princess asked why the old woman did that, and she explained that they were so poor that they had neither food nor clothing, but when she put the pot on the fire and said, “The apples will be ready soon,” the words dulled the children’s hunger so they were patient a while.

The children crying for food went to the princess’s heart and she brought out the napkin and the flask. After the children were full and happy, she cut them clothes with her golden scissors.

“Well!” said the old woman. “Because you have been so kind and good towards me and my children, it would be a shame if I didn’t try to help you up the mountain. My husband is one of the best smiths in the world. Just lie down and rest till he comes home, and I’ll get him to forge claws for your hands and feet to climb the mountain.”

When the smith came home, he set to work on the claws at once, and the next morning they were ready. The princess had no time to stay, but said, “Thank you,” and left. She clung close to the rock and crept and crawled with the steel claws all that day and through the night. Just as she felt so tired that she could scarcely lift hand or foot and was about to fall down, she arrived at the top. There she found a huge plain, full of tilled fields and meadows. It was bigger and broader, and wider and flatter, than she thought was possible. There was also a castle full of workmen of all kinds, swarming about like ants.

“What is going on here?” wondered the princess.

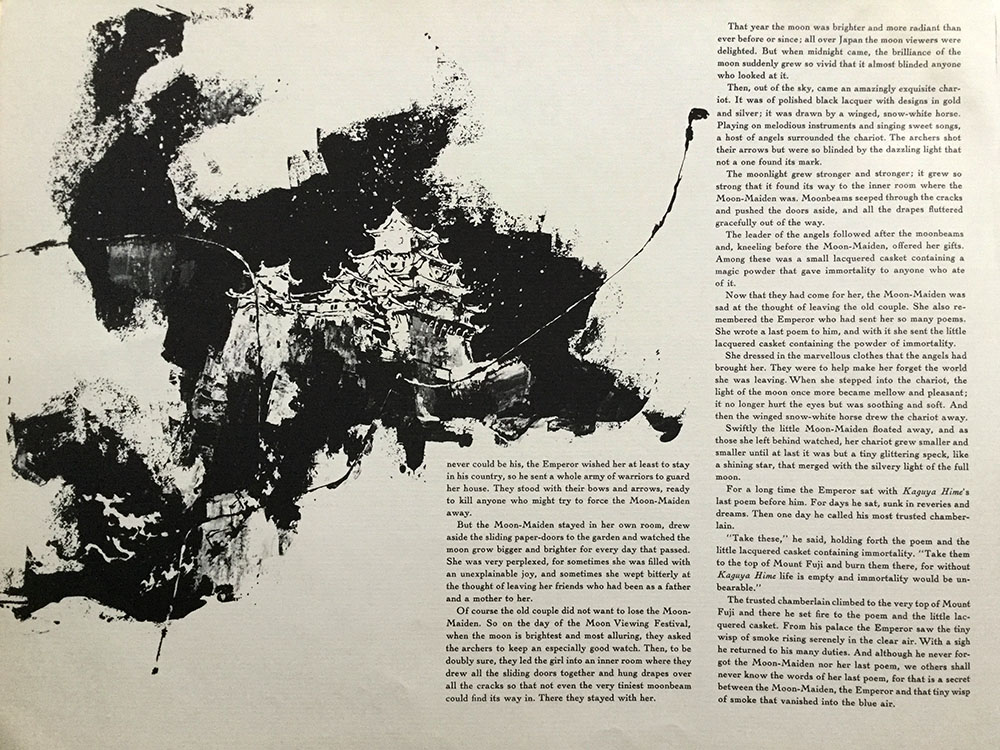

As it turns out, the old troll hag who had bewitched King Valemon lived there, and in three days she was going to hold her wedding feast with him. The princess asked around whether she could speak with the hag.

Everyone said, “No, that is quite impossible.”

So she sat down under a castle window and began to clip in the air with her golden scissors, till the silks and satins flew about as thick as a snow drift.

When the old hag saw that, she had to buy the golden scissors. “Our tailors can do no good at all,” she said. “We have too many to clothe.”

The princess said, “I will not sell the scissors for any amount of gold, but you can have them if you let me spend the night with King Valemon.”

“Yes!” said the old hag. “But I must see him to sleep and wake him in the morning.”

When he went to bed, the hag gave King Valemon a sleeping draught so that he would not open his eyes no matter how much the princess cried and wept.

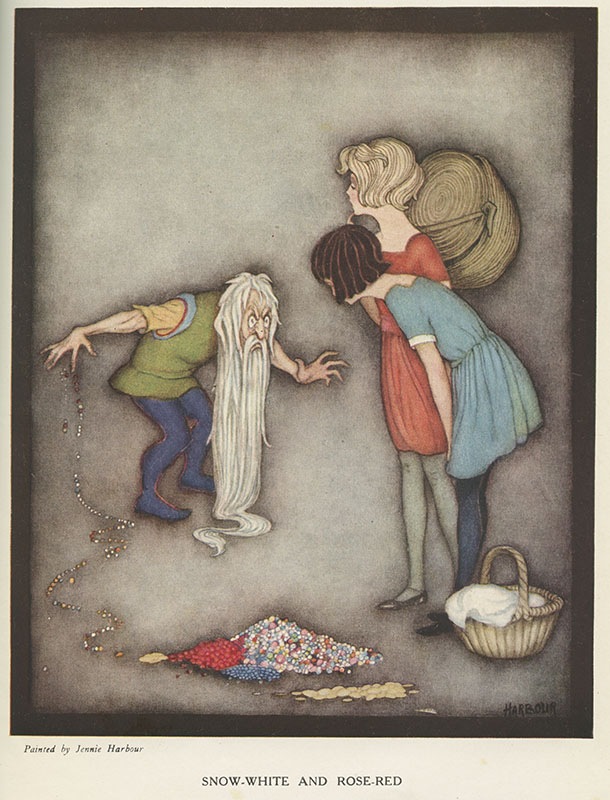

The next day the princess went back under the window again, and began pouring from her flask. It frothed like a brook with ale and wine, and it was never empty. When the old hag saw that, she had to have it. “For all our brewing and stilling, we still have too many to find drinks for.”

The princess said, “It is not for sale, but if you let me sleep with King Valemon that night, then you can have it.”

“Well!” said the old hag. “You may well do that, but I must see him to sleep and wake him in the morning.”

So when the king went to bed, the hag gave him another sleeping draught. It went no better for the princess that the first night. He was not able to open his eyes no matter how much the princess bawled and wept.

But a workmen, who worked in a room next to theirs, heard the weeping. The next day he told the king that the princess who could set him free would come at night.

Outside the castle, it went just the same as it had with the napkin as it had with the scissors and flask. When it was dinnertime, the princess took out the napkin and said, “Napkin, spread yourself out and be covered with dainty dishes.” There was suddenly meat enough, and even to spare, for hundreds of men, but the princess sat down to eat by herself.

When the old hag set her eyes on the napkin, she wanted to buy it. “For all the roasting and boiling, it is worth nothing because we have too many mouths to feed.”

But the princess said, “I will not sell it for money, but if you let me sleep with King Valemon this night, you can have it.”

“Well!” said the old hag. “You may well do that, but I must see him to sleep and wake him in the morning.”

As King Valemon was going to bed, she came with the sleeping draught, but this time he did not drink it and only pretended to sleep. The old hag did not trust him, however, and stuck a pin into his arm to see if he was truly asleep. For all his pain, he did not stir a bit, and so the princess was permitted to see him.

Everything was soon set right between them, and if they could get rid of the old hag he would be free. King Valemon had the carpenters make a trapdoor on the bridge over which the bridal train had to pass, and it was custom for the bride and her friends to be at the head of the train.

As they were crossing the bridge, the trapdoor tipped up with the bride and all the other old hags who were her bridesmaids. But King Valemon and the princess, and all the rest of the train, turned back to the castle and took as much gold and as many possessions as they could carry, and set off for his land to hold their real wedding.

On the way, King Valemon picked up the three little girls from the three huts and took them with them, and the princess understood why it was he had taken her babes away: so they might help her find him. And so they drank their bridal ale both stiff and strong.

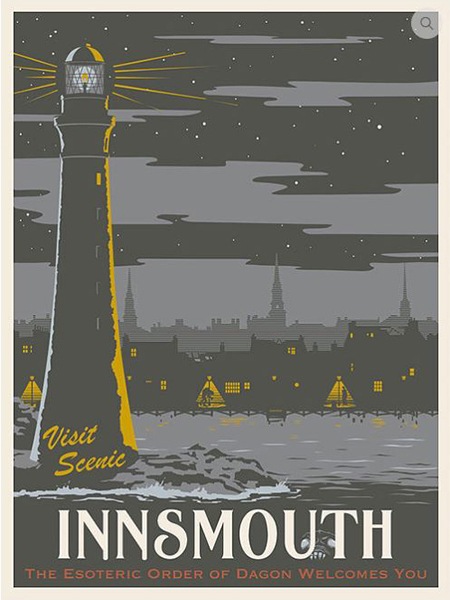

The collection of Norwegian Tales East of the Sun from Taschen, edited by Noel Daniel, adapts an earlier version of the same book, illustrated by Kay Nielsen, with newly sharp versions of and details from the original watercolors. It is quite beautiful (though it lacks Valemon’s tale), as are all the books in that series. Purchases through the links on the pictures below directly support Mirror Mirrored.