The Devil’s Sooty Brother

“But one thing I must tell you: you must not wash, comb, or trim yourself, or cut your hair or nails, or wipe the water from your eyes for seven years.”

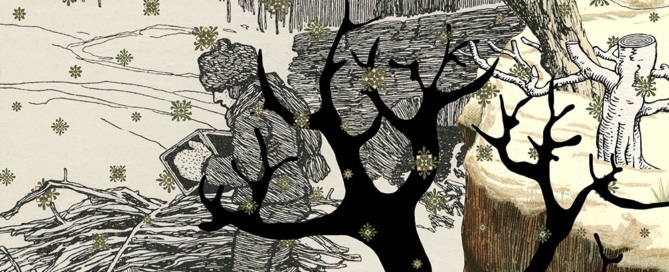

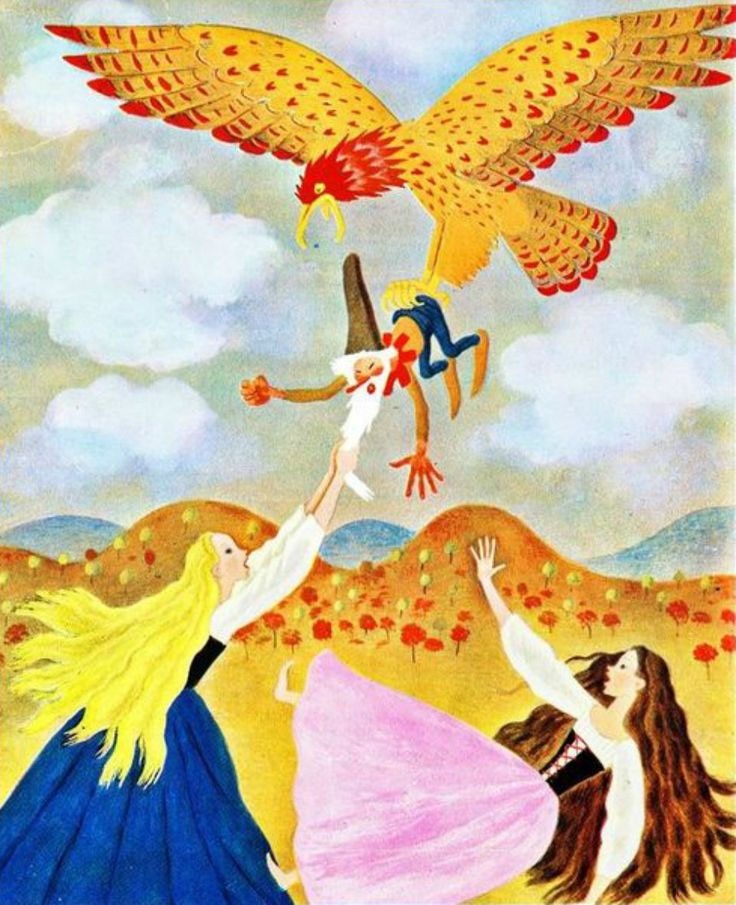

I recently had the pleasure to collage a selection of images from the Grimms’ Tale “The Devil’s Sooty Brother” for Robert Bly’s new book More Than True: The Wisdom of Fairy Tales. This is a less-frequently pictured story, so I had to do a good bit of investigating to find source material for my repiction. I ended up finding images from Otto Ubbelohde (including the flames above), powerful pictures from Albert Weisgerber, Philipp Grot Johann, Franz Stassen, and, maybe most dynamically, from Gustaf Tenggren.

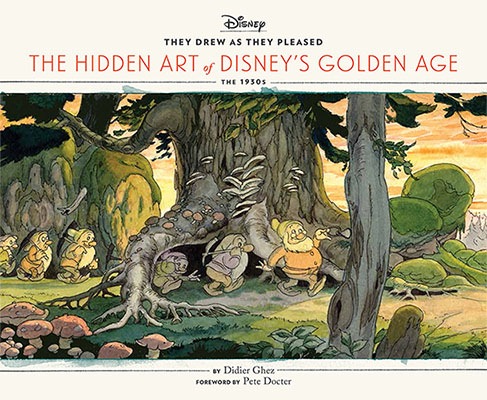

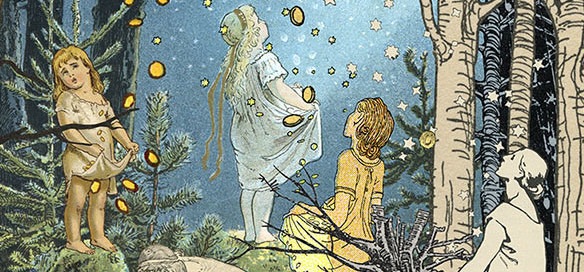

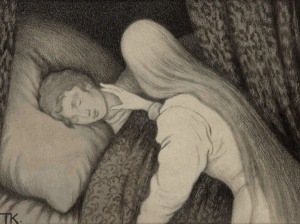

Gustaf Tenggren made this beautiful illustration for the tale in his 1922 Swedish collection of the Grimms’ Tales, which went on to be published in German the following year. Notably, Tenggren later immigrated to America and went to work for Walt Disney, where he was a chief illustrator for Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. You can compare his work for the 1922 illustrated collection with the 1937 movie in the two images below. In the third image, published in the 1955 Little Golden Book Snow White and Rose Red, you can see Tenggren developed his style even further.

With that, I turn to “The Devil’s Sooty Brother,” as collected and retold by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm. In this story, a soldier journeys to the underworld where he earns a living and learns to make music. And, as Robert Bly notes, “When we learn how to play the musical instrument of our body . . . [is] when the man who left the tears in his eyes so he would remember his own grief, the underworld worker, the citizen who now has to forge his own life, gains the entire kingdom.”

The Devil’s Sooty Brother

A disbanded soldier had nothing to live on, and did not know how to get on. So he went out into the forest, and when he had walked for a short time, he met a little man. The little man, who was actually the devil, said to him, “What ails you? You seem so very sad.”

The soldier replied, “I am hungry, but have no money.”

The devil said, “If you will hire yourself to me, and be my servant, you shall have enough for all your life. You shall serve me for seven years, and after that you will again be free. But one thing I must tell you: you must not wash, comb, or trim yourself, or cut your hair or nails, or wipe the water from your eyes that whole time.”

The soldier said, “All right, if there is no helping it.” He went off with the little man, who straightaway led him down into hell. The devil told the soldier what he had to do: he was to poke the fire under the kettles where the hell-broth was stewing, keep the house clean, drive all the sweepings behind the doors, and see that everything was in order. If he even once peeped into the kettles, however, it would go badly for him. The soldier said, “Good, I will take care.”

The old devil went out again on his wanderings, and the soldier entered upon his new duties, made the fire, and swept the dirt well behind the doors, just as he had been bidden. When the devil came back again, he looked to see if all had been done, appeared satisfied, and went forth a second time. The soldier now took a good look on every side. The kettles were standing all around hell with a mighty fire below them, and inside they were boiling and sputtering. He would have given anything to look inside them, if the devil had not so particularly forbidden him. At last, he could no longer restrain himself. He raised the lid of the first kettle slightly, peeped in, and there he saw his former corporal.

“Aha, old bird!” he said, “I meet you here? You once had me in your power, but now I have you,” and he quickly let the lid fall, poked the fire, and added a fresh log. After that, he went to the second kettle, raised its lid a little, and peeped in: his former ensign was in that one. “Aha, old bird, so I find you here! You once had me in your power, now I have you.” He closed the lid, and fetched another log to make it especially hot. Then he wanted to see who might be sitting up in the third kettle and it was actually his general. “Aha, old bird, I meet you here? Once you had me in your power, but now I have you.” And he fetched the bellows and made hell-fire blaze away under him.

So he did his work seven years in hell, and did not wash, comb, or trim himself, or cut his hair or nails, or wash the water out of his eyes. The seven years seemed so short to him that he thought he had only been half a year. Now when the time had fully gone by, the devil came and said, “Well Hans, what have you done?” “I poked the fire under the kettles, and I have swept all the dirt well behind the doors.”

“But you have peeped into the kettles as well. It is lucky for you that you added fresh logs to them, or else your life would have been forfeited. Now that your time is up, will you go home again?”

“Yes,” said the soldier, “I should very much like to see what my father is doing at home.”

The devil said, “In order that you may receive the wages you have earned, go and fill your knapsack full of the sweepings, and take it home with you. You must also go unwashed and uncombed, with long hair on your head and beard, and with uncut nails and dim eyes, and when you are asked from where you come, you must say, ‘From hell,’ and when you are asked who you are, you are to say, ‘The devil’s sooty brother, and my king as well.'”

The soldier held his peace, and did as the devil bade him, but he was not at all satisfied with his wages. Then as soon as he was up in the forest again, he took his knapsack from his back to empty it. On opening it, however, he found the sweepings had become pure gold. “I should never have expected that,” he said, and was well pleased. He entered the town where the landlord was standing in front of the inn. When the landlord saw the soldier approaching, he was terrified, because Hans looked so horrible, worse than a scarecrow. He called to him and asked, “Where are you from?”

“From hell.”

“Who art you?”

“The devil’s sooty brother, and my king as well.”

Then the host would not let him enter, but when Hans showed him the gold, he unlatched the door himself. Hans then ordered the best room and attendance, and ate and drank his fill, but neither washed nor combed himself as the devil had bidden him, and at last lay down to sleep. But the knapsack full of gold remained before the eyes of the landlord, and left him no peace, and during the night he crept in and stole it away.

The next morning, however, when Hans got up and wanted to pay the landlord and travel further, he beheld his knapsack was gone! But he soon composed himself and thought, “You have been unfortunate from no fault of your own,” and straightway went back again to hell, complained of his misfortune to the old devil, and begged for his help.

The devil said, “Seat yourself, I will wash, comb, and trim you, cut your hair and nails, and wash your eyes for you.” When he had done so, the devil gave him the knapsack back again full of sweepings, and said, “Go and tell the landlord that he must return you your money, or else I will come and fetch him, and he shall poke the fire in your place.”

Hans went up and said to the landlord and said, “You have stolen my money. If you do not return it, you shall go down to hell in my place, and will look as horrible as I did.” Then the landlord gave him the money, and more besides, only begging him to keep it secret, and Hans was now a rich man.

He set out on his way home to his father, bought himself a shabby smock-frock to wear, and strolled about making music, for he had learned to do that while he was with the devil in hell. There was, as it turns out, an old king in that country before whom he had to play, and the king was so delighted with his playing that he promised him his eldest daughter in marriage. But when she heard that she was to be married to a common fellow in a smock-frock, she said, “Rather than do that, I would go into the deepest water.”

Then the king gave him the youngest, who was quite willing to do it to please her father, and thus the devil’s sooty brother got the king’s daughter, and when the aged king died, the whole kingdom likewise.

Books related to this post

PLEASE JOIN OUR MAILING LIST

Interested in having your art featured in a Wednesday Wonder Tale post?

Please see submission information here.