I have always found elegance in directness. When I was a five-year-old in kindergarten, I loved going to the National Gallery and looking at the giant Motherwell. I was amazed at how powerful and moving a rather spare artwork could be. When I was a twenty-one-year-old in grad school, I loved Whistler’s Nocturnes, and how much force he could achieve with two days of painting.

Indeed, in the feud between John Ruskin and Whistler, when their disagreements reached the courtroom opposing counsel asked Whistler how he could ask 200 guineas for a two-day painting. Whistler replied, “I ask it for the knowledge I have gained in the work of a lifetime.” He won the trial (but was awarded damages of just one farthing).

As a grad student, when people asked me why I made such slow, intricately detailed work, I related Whistler’s tale and explained that I lacked the knowledge of a lifetime. Older now, I have no such excuse and have embraced the maximalism of horror vaccui as a personal pathology. You can see it at work, for example, in these three Red Cap collages I made for Mirror Mirrored.

Still, I have an immense respect and appreciation for people who can do more with less, which is one reason I find wonder tales so powerful. I especially enjoy fairy tale work by artists whose aesthetic matches this impulse, so here are some minimalist Little Red Riding Hood images that I’ve found floating around the internet.

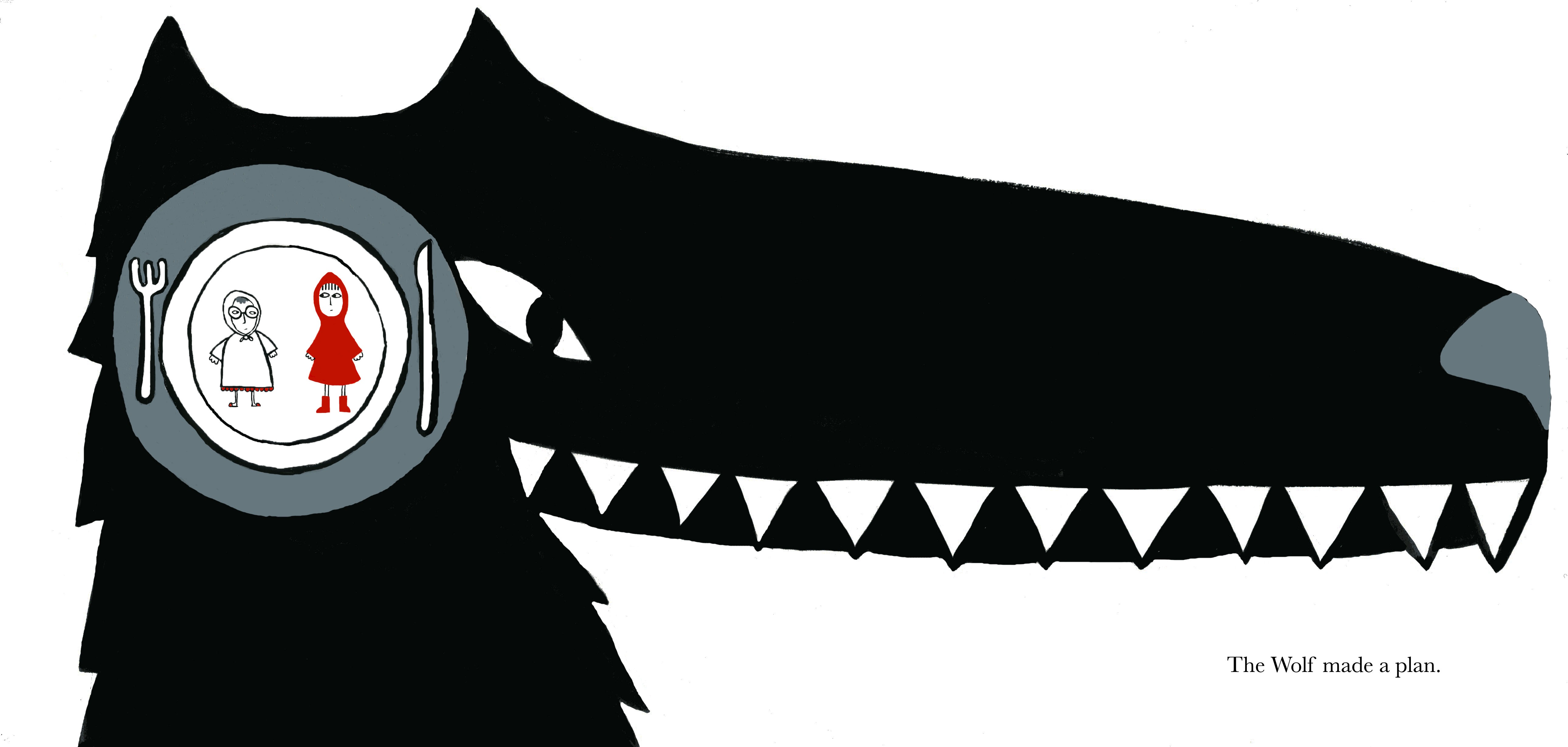

There is also the wonderful retelling Little Red by Bethan Woollvin which, though not quite minimalist, does have one scene in particular that does very much with fairly little. (In this retelling, Little Red is quite the competent ax wielder and thus saves herself from an unfortunate fate rather than waiting on a wandering huntsman. You can buy the book here if you would like to read more, or check out her retelling of “Rapunzel” where the heroine is equally capable of taking care of herself.)

Finally, I would like to share a moment from Picture This: How Pictures Work by Molly Bang. In this classic text, recently revised for a 25th anniversary edition, the author shares her journey from not understanding picture structure at all to studying art and the psychology of art to writing this masterpiece of visual thinking, which Brian Selznick calls “The Strunk and White of Visual Literacy.” The book covers shape, color, direction, number, scale, and so much more, while adeptly describing how each affects the emotion and psychology of the viewer. I advise it to every 101 student I teach. And, as it happens, Little Red Riding Hood and the Big Bad Wolf play a part in the book’s narrative. To conclude this post, I will share a few passages below, but urge you to acquire this phenomenal book for yourself. (You can buy it at Amazon here.)

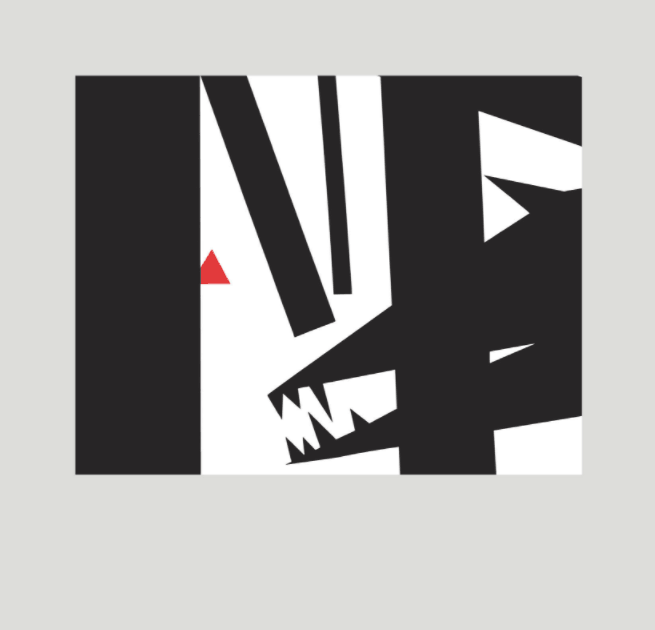

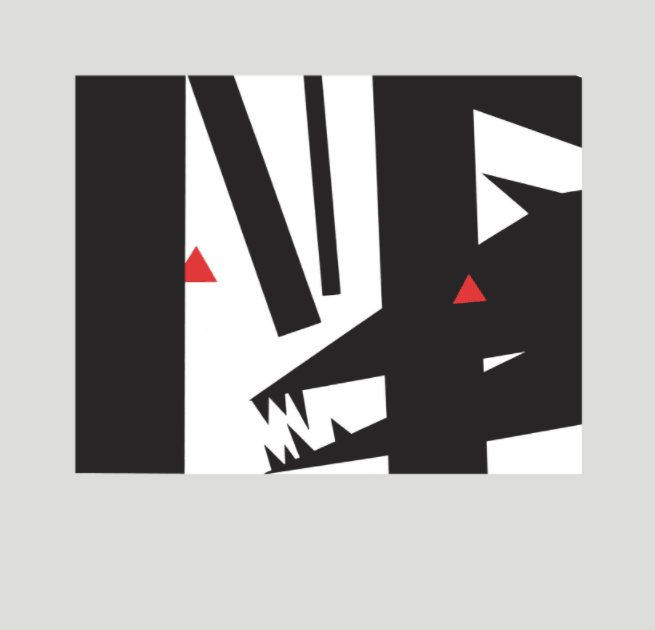

After discussing and showing us various ways to draw Little Red Riding Hood, her mother, and the forest, Bang goes on to describe how she draws the wolf. I have excerpted, below, what she writes about drawing the wolf’s eye.

When we want a picture to feel scary, it is more effective to graphically exaggerate the scary aspects of the threat and of its environment than to represent them as close to photographic reality as possible, because

this is the way we feel things look.

What else does the wolf need in order to look more wolfish?

It needs an eye.

I cut the eye out of the purple paper, since there are three colors available in addition to the white, and the new color attracts our attention. Also, I wanted to use all three colors plus white in every picture.

I made the eye a long diamond or lozenge shape, emphasizing the pointiness of a real wolf’s eye but getting rid of the curves.

But even though wolves’ eyes are often pale blue, it didn’t look right.

Why is this eye so much scarier?

The obvious answer is that it is red, but why should a red eye be so much scarier than a pale-purple eye?

Purple is a milder, less aggressive color than red, but why? Part of the reason may be purely psychological: somehow red excites us. Psychologists have found that people tend to get into more fights in bright-red and hot-pink rooms and tend to eat more in rooms with red walls than they do in rooms with paler colors. Part of the reason may be that we associate red with blood and fire, so this is a bloody, fiery eye rather than an eye associated with flowers or with the evening sky. Maybe it’s because we’ve seen drunken, bloodshot eyes, or eyes reflected in a campfire, and those were red. In some fairy tales, the eyes of witches are described as being red. Red eyes are unnatural, and unnatural things make us wary. And red is an energetic color, a color with agency, so while all-white eyes are also unnatural, it is red eyes that have the energy to be hostile.

But I notice something else with the replacement of the purple eye with the red, something I wasn’t expecting: I immediately associate Little Red Riding Hood with the wolf’s eye, in a way I didn’t before. They go together. Now the eye is looking at her.

The strong association is almost solely due to the color; when I made the eye round but still red, I associated it with Little Red Riding Hood the same way.

What happens if the eye is made exactly the same color and shape as Little Red Riding Hood?

The wolf looks stupid now, or surprised, or maybe happy. Its glance is no longer pointed at its prey. Certainly it is not nearly as evil-looking as it was before. The picture feels very different, and yet all that has been changed is the shape of the eye.

A more disconcerting effect to me is that the two red triangles are now so alike, and I associate them so much with each other, that they disassociate from the rest of the picture. They are no longer meaningful elements. I see them not so much as Little Red Riding Hood and a wolf’s eye now, but more as two red triangles that float up and out of the picture.

I return to the wolf with the more pointed red eye.

And with this beautiful image, I will conclude the post. Thank you so much for reading.

You can find more information about the minimalist illustrators and artists mentioned in this article at these sites: Molly Bang, Indre Bankauskaite, Noma Bar, Pablo Gauthier, Alessandro Gottardo, Christian Jackson and more information on his series by My Modern Met here, Lowe/SSP3 and more information on its series by Chic Type here, Pinto Sketches, Dina Waluyo, and Bethan Woollvin.

Books mentioned in this article:

Marvelous! Thank you for this.

Glad you enjoyed it Jan 🙂