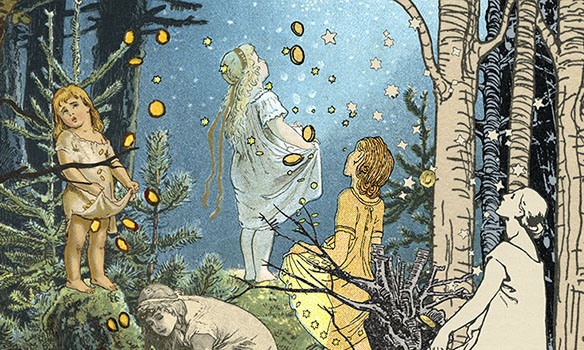

A collage built around an illustration of “The Golden Key” by Otto Ubbelohde. Prints available here.

In the winter time, when snow lay deep on the ground, a poor boy was forced to go out with a sled to fetch wood. When he had gathered the wood together and packed it, he wished, as he was so frozen with cold, not to go home at once, but to light a fire and warm himself a little. So he scraped away the snow, and as he was clearing the ground, he found a tiny, golden key. He thought that where the key was, the lock must also be, and dug in the ground and found an iron chest. “If the key does but fit!” he thought. “No doubt there are precious things in this little box.” He searched, but there was no keyhole. At last he discovered one, but it was so small that it was hardly visible. He tried the key, and it fit exactly. He turned it round once, and now we must wait until he has unlocked it and opened the lid, and then we shall learn what wonderful things were lying in that box.

“The Golden Key” is the last story in the Grimms’ collection. Art historian Carol Mavor, with a nod to Roland Barthes, explains in her book Aurelia that this “unfinished gesture” turns the reader into a writer because it “demands the reader to write, to imagine, their own words that will fill the ‘little iron casket’ with their desires.” She then continues with the idea that withholding the “wonderful things” in the box has a touch of sadism because we “desire to know.” I personally tend to very much enjoy the possibility of what is in the box and think that, maybe, knowing specifically what was inside would never be quite as satisfying as leaving it to our imaginations. Did the box contain the original Grimms’ Tales? Borges’ “Library of Babel”? Something not yet discovered? But, as far as endings go, Peter Straub has offered a very satisfying conclusion. As fairy tale scholar Maria Tatar points out in The Annotated Brothers Grimm, Straub continues “The Golden Key” in his novel Shadowland. He writes that “[e]very story in the world, every story ever told, blew up out of the box. Princes and princesses, wizards, foxes and trolls and witches and wolves and woodsmen and kinds and elves and dwarves and a beautiful girl in a red cape, and for a second the boy saw them all perfectly, spinning silently in the air. Then the wind caught them and sent them blowing away, some this way and some that.”

Undone by Sarah Fagan

Portable Miracle Filling, et al. by Sarah Fagan

When Sarah Fagan decided to reimagine this story for Mirror Mirrored, she took two very different approaches before settling on a final piece. First, she painted a white paper box, unfolded against a white background. She explained that, like the Tao Te Ching which states, “It is the empty space that makes the bowl useful,” she saw utility in emptiness. In a paper box’s unconstructed state, it is potential and has no material function. When it interacts with a human hand, however, it can become a repository for anything. It is both a blueprint for something and a thing itself.

Second, the piece that she ultimately decided to include in Mirror Mirrored was the traced outlines and creases of several unfolded boxes laid on top of each other, each layer of stacked boxes colored in with four different color pencils. In this piece, she both obliterates existing forms (the now abstract boxes) and creates a new one. She sees it as a way to free each box from the singular purpose it was created for and throw it into a perpetual self-examination of its nature: the forms organize and reorganize, attempting to make sense of themselves as we try to make sense of them. Maybe, she continues, these transformed boxes are not so unlike us: constantly structuring, compartmentalizing, and trying to understand our own lives. Thus, Fagan has decided to interpret “The Golden Key” not as a story looking outward, where the viewer imagines some far away magical story, but instead focuses inward, to see what the results of our imagination say about ourselves.

Selected books from this post

GET WEDNESDAY WONDER TALES IN YOUR EMAIL INBOX

Interested in having your art featured in a Wednesday Wonder Tale post?

Please see submission information here.

Leave A Comment