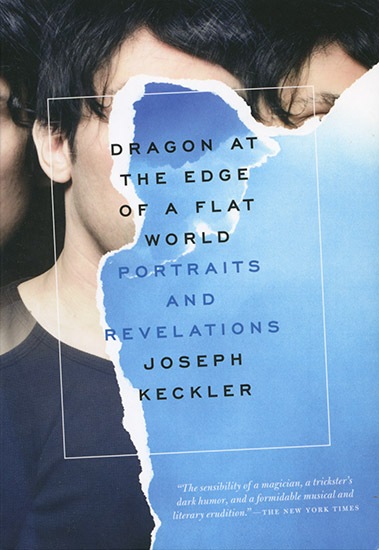

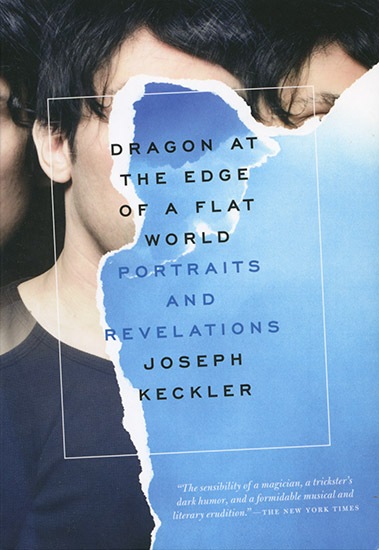

I have a copy of a brand new book, Dragon at the Edge of a Flat World, sitting on the edge of my desk. Inside it is inscribed: “Hope we stay in the same reality. Love, Joseph.” At the time, I did not fully appreciate the extent to which Joseph Keckler, the author, is a dimension-travelling wizard. But I already had inklings.

A Singular Meeting

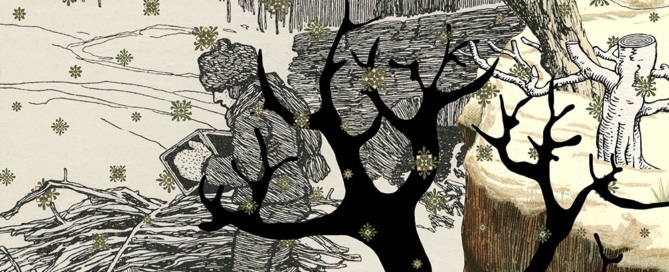

Published by Turtle Point Press

Three days earlier, late one evening in Austin, Texas, I received a text message: “Hi, This is Joseph.” Joseph and I had never met, but he is the friend of a good friend and created a beautiful piece for Mirror Mirrored. Also, a year and a half earlier, I had arranged a performance for him at a DC gallery on the only night I can remember the entire city’s metro system shutting down (the small group that managed to make it to the event was treated to a very intimate showing).

As it turns out, Joseph was in Austin for his book tour and thought it would be a fantastic opportunity to get to know each other. I agreed, and because he was staying on the other side of the river suggested we meet downtown—halfway for both of us. He happened to know a chef, however, about a thirty minute walk from my apartment, which suited me just fine. He took a ride share.

Upon arriving at the restaurant, I did not see Joseph—who my friend had described as looking like a more talented and refined Johnny Depp. On that particular dark evening, I was very much wondering exactly what talent looked like. The answer was a thin figure in a leather jacket casually wandering about the street at the edge of the park. I waved and we went in together.

As the only patrons in the dining room, we were seated at a small table in the middle of the room. Well, there was a wild party that was technically in the same room, but a series of large white sheets had been draped across the space such that all we could see were shadowy ghosts cavorting about sounding rather like a group of Florida retirees. We turned to the wine menu.

After our server recommended an Italian red that neither of us could pronounce, a woman brought out a bottle. She poured two glasses, said “May you chase the devil off the mountain,” and left. After confirming with each other the reality of what had just happened, we proceeded to drink several glasses of wine over several plates of pasta. When we each ordered a second glass, we took the opportunity to inquire with this beverage bearer if she had indeed encouraged us to shoo Satan away. She said yes, as that was the literal translation of the Italian wine we were drinking. She then pulled out her glasses, examined the label of wine as if to confirm herself, and without saying anything further danced away.

The devil on the mountain

We turned to other topics. We agreed, as an initial matter, that we wanted to be neither cannibals nor cannibalized, nor did we want to take a one-way trip to Mars. Apparently feeling this established a reasonable common ground, Joseph dispensed with trivialities. He leaned in and asked, “Do you remember a series of children’s books with bears from when you were a child?”

“Yes,” I replied. “Paddington.”

“Not that one, the other one.”

“The Berenstein Bears?”

“Except there were no Berenstein Bears.”

I was intrigued. Joseph then explained to me that there was a children’s book series called the “Berenstain Bears,” but that the “-stein” bears were merely markers of an alternate reality that a large portion of us had experienced which how somehow been convoluted with the one we live in now. (For a fuller explanation of this phenomena, known as the Mandela effect, please see here.)

As if checking my reality credentials, he continued: “And do you remember what the evil queen asked the mirror in Walt Disney’s Snow White?”

Full of certainty, and additionally armed with having just looked at the original German, I replied, “Mirror, Mirror, on the wall…”

Joseph excitedly cut me off, “But actually it was ‘Magic Mirror on the Wall!'” He explained that these moments where the alternate realities break through give themselves away by being twice too witty about seeping through “stains” and “mirrors.” We solidified a potential friendship by establishing that we were from the same corrupted timeline.

Magic Mirror

We then decided to make sure we finished chasing the devil off the mountain. After accomplishing that task, we switched to coffee. We talked for a while longer—about growing up, reclaiming stolen time, and where art comes from. Then, as the very lively ghost party across the room wound down, it was time to go.

Leaving the restaurant, Joseph joined me on the walk back toward my apartment and then decided that, as the night was still night, he would meander three hours back across the river to where he was staying. We said farewell for the moment, and I told him I was looking forward to seeing him again at his reading.

Joseph in Amazing Technicolor

Three days passed. I arrived a little too early at the art gallery, so I took the opportunity to enjoy a local beer and hide in the corner of the room where I could comfortably watch Joseph. I had heard that nothing can quite prepare you for a Joseph Keckler performance, so I was at least prepared in my unpreparedness. The crowd, however, had not been so similarly warned.

As Co-Lab Projects introduced the plain-spoken Midwesterner, the crowd was happily engaged and quietly humming in the way that happens when several groups of people are having soft conversations with each other all at once. Joseph started reading, and Joseph is quite a good reader.

Co-Lab Projects

Then, Joseph started singing. The humming vanished.

It is beyond my writing capabilities to describe the power or emotional weight of a Joseph Keckler performance. If the weird, kind of dorky but probably actually cooler-than-you kid from high school also turned out to be quite handsome, the most talented singer you’d ever heard with a voice whose “range shatters the conventional boundaries of classical singing” according to the New York Times, but is still kind of dorky, then maybe you get the idea. (The videos Shroom Aria and Strangers from the Internet below, though singularly special in a different way, do not quite do his live performance justice.) As he read from his book, performed, sang a heartbreaking aria about his lover’s GPS, and closed with David Bowie from atop a stool, I wish I had been sitting down so that I could stand up to clap. Luckily, most of the audience who had been sitting felt the same way. After the show, I bought his book, Joseph signed it to assure me we were at that particular moment in the same reality, and he was whisked away to another city and a larger venue.

The Edge of the Flat World, from the Safety of an Armchair

Some time later, taking sufficient time to delight in the anticipation of reading the book, I sat down in a comfortable (if rather hideously patterned) recliner, turned on my studio lamp, and jumped into Joseph’s book. You might say, much like Alice, I rather fell into his universe. After my trip, I am no longer assured we have always been in the same timeline.

In Joseph’s world, importantly, a dragon at the edge of a flat world resides at the “outskirts of possibility”—not safely walled away inside impossibility. At this edge, conveniently accessible by Brooklyn mass transit, there is also a McDonald’s. In this reality, ghosts (real ones), Sjögren’s syndrome sufferers, Fiji mermaids, diplomats, vodka-spitting bartenders, and artists who burn down other artists’ work in fancy museums, fluidly weave in and our of our lives.

The fire

As he starts the book, a collection of twenty interconnected moments from his own life, we find a three-year old Joseph watching his house burn down in the middle of a Michigan winter as he and his family lose their possessions in the flames (he, as a three-year old, has somewhat less to lose than his mother, father, or brother, though there is mention of a special Gooney Bird). As we conclude the novella, he is back in the Michigan winter, years later, bearing witness as the “chief mourner” to passengers on a train losing their Happy New Year as the train hurtles across time zones without ever hitting midnight.

Between these two events, there is much joy, a good bit of loss, several cats, and a lot of New York City. Joseph takes us on a wide-ranging journey through our world. He is constantly referencing exterior markers, such as Zorro’s alter ego Don Diego, the widow Mrs. Gummidge from David Copperfield, Dr. Moreau, and Cleopatra—these in the space of two paragraphs—almost as if he is desperate to confirm that the world he has experienced is actually the one he is in. (I briefly considered stopping at each work Joseph referenced, watching it or viewing it in its entirety to fully appreciate the point, then resuming his book, but decided I would have to similarly consume each work referenced in the references and might also have to learn a few new languages to complete this process, so threw in the towel.)

Joseph’s art, it would appear, is inspired by events outside himself. He replaced prime-time television with personalities in his daily life and thus takes unusual jobs such as working for a blind gallerist, he wanders the streets at night until he passes out, defeated at last, and he embraces cross-dimensional traveling via magical realism (where, possibly, everyone sings beautifully rather than talking and is where Joseph honed his craft).

In the course of those experiences, he welcomes us with spectacle, wizardry, and wit, then gently directs us to deeper, quieter places, best suited for you to experience yourself rather than read about in a book review. As Joseph attempts to discover himself, by changing modes of sexuality and switching from vampire t-shirts to baggy “in” clothes to tribal necklaces, satanic rings, rotary telephone cords, and tiger stripes on jeans drawn with a Sharpie, we learn something about both ourselves and each other in the process. The book is a wonderful read and I suggest it to you without hesitation. You can find it here on Amazon.

Oh, and if you ever find yourself up by Plainwell, Michigan, there is a yard where a dog poops rainbows right down the way. Rainbows that, in their afterlife, have become nuggets of radiant filth, fallen from the sky. And though I have never been there, if you find the particular rabbit hole that shows you the way, please drop me a line.

A rainbow’s end

All photographs except the cover of Dragon at the Edge of a Flat World are by Corwin Levi. The book cover’s photograph is by M. Sharkey and defaced by Joseph Keckler.